META-SELECTION IN HUMAN EVOLUTION

pp. 339-354.

(Copied with permission)

ALTRUISM AND THE HYPOTHESIS OF

META-SELECTION IN HUMAN EVOLUTION

Ferdinand Knobloch, M.D.*

*Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver,

Canada; Chairman and Training Analyst, Canadian Society for Integrated

Psychotherapy and Psychoanalysis (a member of the International Federation

of Psychoanalytic Societies); Past President, Psychotherapy Section, World

Psychiatric Association.

The problem of altruism in human evolution, although discussed from the

very beginning of Darwinism, has not reached a generally recognized solution

until today. I will propose the meta-selction hypothesis as a possible

partial answer. Heuristically, my study of transference and resistance

contributed to its formulation.

THE DARWINISTS PUZZLE OVER ALTRUISM

Since the very beginning, evolutionary theory has been concerned with

the problems of selfishness and altruism. Charles Darwin (1871) concluded

that selfish individuals are favored by evolution. At the same time, he

had no doubt "that tribe including many members who, from possessing

in high degree the spirit of patriotism and fidelity, obedience, courage,

and sympathy, were always ready to give aid to each other and sacrifice

themselves for the common good, would be victorious over most other tribes;

and this would be natural selection" (p. 166). Wilson & Sober

(1994) summarized the issue laconically: "Altruism involves a conflict

between levels of selection. Groups of altruists beat groups of nonaltruists,

but nonaltruists also beat altruists within groups" (p. 599).

But Darwin's comments are puzzling and he lets us down by failing to elaborate,

complains Cronin (1991) in her book prefaced by J. Maynard Smith. She

suspects group selectionism which she rejects, scorning it as "greater-goodism."

Cronin joins Hamilton in concluding that Darwin dealt with human altruism,

saw the problem, discussed it, but left it unsolved (p. 327).

ARE WE BORN SELFISH?

Dawkins (1976, 1989), who represents the prevailing opinion of contemporary

sociobiology, says: "Be warned tthat if you wish, as I do, to build

a society in which individuals cooperate generously and unselfishly towards

a common good, you can expect little help from biological nature. I am

not advocating morality based on evolution. Let us try to teach generosity

and altruism, because we are born selfish (p. 3)." Dawkins talks

here about altruism in the usual sense of the word, psychological or motivational

altruism, and not about evolutionary altruism and egoism, the "selfish

gene," which is broadly accepted and will not be discussed here;

see Sober and Wilson, 1998).

Of many authors who have similar views, only one, Badcock (1986), will

be mentioned here because of his attempt at psychoanalytic explanation.

Our motives are selfish, he claims, but they are repressed and so we believe

we are altruistic. According to de Waal (1996), what Badcock asserts is

that we are sophisticated hypocrites (p. 238).

The problem is not only theoretical and the educators are worried. They

ask: What shall we tell our children? (Thiessen, 1996). And Hrdy (1996),

a prominent student of evolution, comes to a surprising and controversial

conclusion:

I question whether sociobiology should be taught at the high school level,

or even the undergraduate level, because it's very threatening to students

still in the process of shaping their own priorities… The whole message

of sociobiology is oriented toward the success of the individual. It's

Machiavellian, and unless a student has a moral framework already in place,

we could be producing social monsters by teaching this. It really fits

in very nicely with the yuppie "me first" ethos, which I prefer

not to encourage. So, I think it's important to have a certain level of

maturity, with values already settled, before this kind of stuff is taught.

I would hate to see sociobiology become a substitute for morality. It's

a nasty way to live ( p. 19).

VARIETIES OF ALATRUISM

When talking about "altruism" we have to distinguish between

psychological (motivational) altruism, that is "altruism" as

we understand in ordinary language, and evolutionary altruism, describing

behavior which increases the fitness of others at the expense of the fitness

of the altruist. In that regard, the present-day sociobiology distinguishes

sharply between kin and non-kin members of the group. Altruism among kin

members, kin altruism, presents no theoretical problems because, even

if the individual's altruistic behavior leads to decreased fitness, it

increases, if all goes well, the fitness of one's children or other kin

members, so the same genes are preserved (inclusive fitness). In contrast,

nothing else can exist among non-kin members than reciprocal altruism,

that is, an exchange of equivalent values - something for something else

- or the lineage of altruists would die out.

But do people always bargain for reciprocal compensation? Are not people

sometimes inclined to help others, without thinking on reciprocal compensation,

and accepting gratefulness as reward? That is supported by such empirical

studies as of Caporael and al. (1989) and Batson and Shaw (1991). However,

the discussion is clouded by traditional philosophical struggles among

hedonism, egoism and altruism, as described by Sober and Wilson (1998)

who, however, did not quite escape from it, in my opinion. Though I accept

their tentative conclusion that people are sometimes genuinely altruistic,

I do not use the tern "altruism" as they do, which does not

allow for any kind of reward, agreeing with Krebs (1961) and Mook (1981)

that egoism and altruism is a false dichotomy.

. The standard argument of sociobiologists against any altruism among

non-kin members beyond reciprocal altruism is that individuals, being

handicapped by having altruistic genes, would die out. But Sober &

Wilson (1998) argue that it is not necessarily so. The authors are representatives

of the resurrected group selection theories, which since the sixties was

declared as outdated-- not theoretically impossible, but so improbable

that it does not need to be considered . They accept that in each group,

the number of altruists gradually diminishes. However, the total number

of altruists in all related groups grows. This counter-intuitive result

is based on Simpson's paradox (p. 25). That this, however, can take place,

is conditioned by1. there must be a population of groups; 2. the groups

differ in the proportion of altruists; 3. there is a positive correlation

between number of altruists and the success of the groups (as Darwin envisaged);

and 4. the groups interact in certain limited ways (p. 23).

Although the argument of Sober and Wilson seems persuasive to me, and

although it seems to me -- as the erratic path toward truth is often zigzagging

-- that the naive group selectionists of the past were replaced by fanatics

of individualism (scornful of "greater-goodism "of group selectionists),

I will leave the final solution of this controversy to the expert biologists

(see the reviews of Sober and Wilson's recent book, e.g., by Maynard-Smith,

1998; Trivers, 1999ab;

and the answer by Wilson and Sober, 1999).

Luckily, the hypothesis of meta-selection, based on the idea of breeding

by higher-order breeders, namely groups-as-a-whole, is immune to the outcome

of this controversy; for this reason, the controversy does not need to

be described here in detail.

HE PATH OF META-SELECTION

One of the stimuli to the meta-election hypothesis came from re-reading

the first chapter, on domestication, in Darwin's (1859) Origin of Species.

He writes: "The key is man's power of accumulative selection: nature

gives successive variations; man adds them up in certain directions useful

to him. In this sense he may be said to have made for himself useful breeds…"

(p. 47).

Let us imagine that the breeders who made for themselves "useful

breeds" were supernatural breeders of humans, Biblical tribal gods

- Yahweh, Baal,

or Dagon. These tribal gods competed among themselves for the success

of their tribes much more fiercely than the breeders of racehorses do.

We are told that with the assistance of Yahweh, in the city of Jericho,

all citizens, including children, were killed (Joshua, 6:21). However,

they prescribed altruism to the members of their tribes ("love thy

neighbor"), submission to authorities, and other rules enhancing

the tribal cohesion and fitness. By dispensing rewards and punishments

extended to future generations (viz. the Yahweh of the Old Testament).

These supernatural breeders do not need to exist to be effective, if they

are prescriptive symbols for the tribes functioning as higher-order breeders.

In fierce competition with other groups, they are driven to create selectively

cohesive groups. In order to be cohesive, the group demands the bonding

of members with altruism beyond reciprocity to non-kin members - and this

is what higher-order breeders achieved. This is a more flexible and rich

alternative solution to that of the mega-communities of ants and bees,

characterized by extreme altruism, but governed by rigid rules, in their

undertakings as huge "family businesses."

When using the metaphors of Biblical gods, we must not forget that these

complex heavenly figures are of recent origin, not more than ten thousand

years old, whereas the EEA (era of evolutionary adaptedness) during which

human traits developed, stretched for hundred of thousands of years. We

have to assume that these gods had primitive predecessors or equivalent

ways to drive the group to be more and more cohesive and function better

as units.

Good organization requires some hierarchy. Now, who does the organizing

and why? The organizers (roughly synonymous: leaders, power coalition,

power elite, ruling class, governing class, and economic and cultural

brokers) are those who have formal or informal power to influence planning,

make decisions and coordinate the activities of the members, resulting

in the distribution of benefits and costs. These leaders care about the

welfare of the group as a whole, at least to the degree they are sufficiently

rewarded and can retain their power in the group. The success of the group

brings rewards to its members (though often grossly uneven), and with

it increased inclusive fitness.

Who pays for the organizing efforts? In clubs, there is a club membership

fee, in political states, the government collects revenues. In the process

of evolution, with the help of the organizers as executors influencing

the distribution of benefits and costs, new rules of meta-selection, different

from the rules of natural and sexual selection, emerged. These rules created

a disposition to pay the "membership fee" willingly, even with

pleasure. To act with concern for the welfare of the group and to enjoy

receiving and showing altruism beyond reciprocity, to do good to others

and receive their appreciation and gratitude, is often regarded as one

of the life's greatest pleasures. Indeed, it even affects positively one's

physical health (Selye, 1956).

The leadership enjoyed special rewards and privileges, though the leaders

of EEA would blush if they would see the privileges of kings of the first

civilizations with their thousands of concubines and slaves.

It is further assumed that meta-selection is a continuation of a process

which started long before human development. Even in chimpanzees, and

presumably still more among hominids, there are signs pointing in the

direction of meta-selection. As de Waal (1996) observes about chimpanzees:

"Undoubtedly, prescriptive rules and a sense of order derive from a hierarchical organization, one in which the subordinate pays close attention to the dominant. Not that every social rule is necessarily established through coercion and dominance, but prototype rule enforcement comes from above" (p. 92).

In a simplified form, most of the basic features of human social systems

can be seen in chimpanzee groups as described by de Waal (1982, 1989,

1996). For example, vis-a-vis the development from dominance to leadership

(1996):

I learned from this development not only that the control role can be

performed by the second-in-command but also that the group has a say in

who performs it and how. It appears to be one of those social contracts

in which one party is constrained by the expectations of the others. As

a result, the control role may be regarded as an umbrella shielding the

weak against the strong.... It is as if the group looks for the most effective

arbitrator in its midst, then throws its weight behind this individual

to give him a broad base of support for guaranteeing peace and order.

In this sense, then, there is a payoff to the control role: instead of

coming from powerful friends, the return favor comes from those who at

first glance appear powerless. Although high-ranking individuals have

disproportionate privileges and influence, dominance also depends to some

degree on acceptance from below. (p. 130).

Though the rewards and coercion from above is essential for the development

of meta-selection, it would be erroneous to interpret the hypothesis of

meta-selection as ascribing the exclusive shaping power to the group organizers.

Even in chimpanzees, the pressures from other roles - peers, sexual partners

and even from the subordinates - have shaping effect. As de Waal (1996),

comparing humans and chimpanzees, says:

Subordinates have a way of joining forces: alliance formation, a characteristic

of the primate order, blunts absolute power. Originally, alliances chiefly

served the acquisition of dominance.... The same instrument, however,

permits lower echelons to rise up against and even overthrow rulers. Such

use is already visible in the chimpanzee...(p. 127).

In short, the dismantling of despotic hierarchies in the course of hominoid

evolution brought an emphasis on leadership rather than dominance, and

made the privileges of high status contingent upon services to the community

(such as effective conflict management) (p. 132).

The hypothesis of meta-selection assumes that there was never a time in

human development without hierarchical structure, and that is also the

opinion of de Waal (1996) about our past. This is what he says about the

so-called egalitarian groups of hunter-gatherers: " Status differences

are never completely abandoned, however. Instead of having no hierarchy

at all, egalitarian societies occupy one end on a spectrum of dominance

styles running from tolerant to despotic"(p. 125).

A group competing for its survival has to be hierarchically organized

and that is propelled by the general desire to have power over others,

and by differential abilities to fulfill the task and maintenance functions

of the group. A remarkable tightening of the hierarchy took place after

the hunters-gatherers era, but the last centuries have witnessed an opposite

trend, though an undulating one, in which there has been a flattening

of the pyramid of power with an increasing sensitivity to the needs of

every individual.

What are the pressures of the leadership on the group members, through

dispensing rewards and costs, including punishments? 1. It requires de-emphasizing

the difference between kin and non-kin.(NOTE 1) 2. It establishes the

exchange rates in social exchange, and that is the basis of the accepted

rules of fairness, justice and morale behavior which infiltrate the group

schema (see NOTE 2) of individuals. 3. It reinforces the hierarchical

structure. 4. It creates new benefits, both material and symbolic, for

those who protect the group, improve its life and bring sacrifices, and

show altruism.

The outcome of these pressures is the development of altruism beyond reciprocity,

the development of sympathy (responsiveness to the needs of others in

self-other relationship) and empathy (responsiveness by identification),

and feeling rewarded by helping others, particularly when they express

their gratitude. Meta-selection creates an elaborate group schema (NOTE

3), which is a way for the group to control the individual 24 hours a

day. The harmonious relationship with one's group and with one's group

schema protects one from the fear of ostracism, brings a feeling of security,

and contributes to physiological balance.

The present hypothesis (Knobloch, 1996), attempting to explain altruism

beyond reciprocity toward non-kin members of one's group, proposes meta-selection

as a third kind of human selection, in addition to natural and sexual

selection. It is assumed to be an intra-specific selection, similar to

sexual selection, but whereas sexual selection is individual selection,

meta-selection is thought to be a special kind of group selection, a process

of self-domestication

or self-socialization.

Tendencies based on meta-selection will be often in conflict with tendencies

based on natural and sexual selection. This is nothing new: body shapes,

ornaments, color and behavior created by sexual selection sometimes interfere

with the safety dictated by natural selection - a peacock's tail is an

example (summarized by Cronin, 1991, p. 227).

Similarly, tendencies shaped by natural selection may be in conflict with

those shaped by meta-selection, e.g., a conflict between self-interest

and altruism which pushes hard to encourage sacrifice for the good of

the group. It seems that the meta-selection hypothesis can best explain

such extreme variants as self-sacrifice, kamikaze, mass suicides of the

members of religious sects, and possibly also self-restraint, asceticism,

and self-purification (Lopreato, 1984). Altruism toward the group is also

often in conflict with nepotism, something which is not news for politicians

who often struggle and fail in these conflicts, longing nostalgically

for the privileges of kings.

An example of the conflict between sex selection and meta-selection is

the conflict between a daughter of high social standing, attracted to

a man low in the hierarchy, and her parents, staunchly defending the stability

of the social system.

The dilemmas of harmonizing the tendencies flowing from natural, sex and

meta-selection are existential dilemmas of human destiny, which we face

every day. Different circumstances and cultures call for different solutions.

This may be one of the causes why evolution promoted a mix of behavioral

phenotypes (Wilson, 1996).

The existence of pro-social behavior and altruism has often been regarded

as a challenge to evolutionary theory. What selection pressures could

possibly mold human nature to act contrary to a radical self-interest?

The argument is that meta-selection creates new conditions of social life

in which the right mix of altruism and self-interest leads to higher inclusive

fitness than self-interest alone. Selfish persons not liked or ostracized

by their group do not do well (Frank, 1988). Throughout the ages and perhaps

more than ever in this century, millions of people risked their lives

in war, partly because to avoid fighting was even more dangerous, partly

to avoid ostracism.

Because of the high value of altruism, pretending to be an altruistic

person or pretending to have altruistic motives may be the most frequent

kind of cheating. And the deceit of others may be combined with self-deceit,

such as a rationalization leading to a belief that one's motives are noble.

Such self-deceit leads to behavior which makes the ostensible intentions

more convincing.

So the Darwin's idea quoted earlier: "Groups of altruists beat groups

of nonaltruists, but nonaltruists also beat altruists within groups"

needs a slight modification : The nonaltruists who beat altruists within

groups must be successful cheaters pretending altruism- and such talent

is rare!

If the hypothesis of meta-selection is correct, we are born not only selfish,

as Dawkins claims, but also altruistic- and volatile. It seems that meta-selection

took great deal care of generosity and altruism which Dawkins was worried

about. Without it, his program of education would be doomed …

DISCUSSION.

Does the postulate of meta-selection meet the conditions which have been

set as necessary for group selection? First of all, there should be a

population of groups with variable qualities of cohesion and inclusive

fitness. There certainly was such a population of hunter-gatherers in

groups with variable ability to deal with the task functions and maintenance

functions of the group. Clearly, in the context of fierce competition,

groups which were better organized and cooperative, as Darwin noted, survived

and had higher inclusive fitness.

Second, was there a high rate of extinction? This can be answered positively.

Even today, the rate of extinction is high among hunter-gatherers, between

2 and 30 percent every 25 years, as Soltis, Boyd and Richerson (1995)

found studying clans in New Guinea.

Thirdly, is there small migration between groups? This can be answered

less satisfactorily. It can be assumed that in raids the men were killed,

but many non-pregnant women were taken as booty and through their children

slowed the genetic changes in the process of meta-selection. Nonetheless,

even so, this form of selection was powerful enough - the more so, that

it was not random, involving, as in breeding animals, an element of human

goal-directedness ("the commands of the tribal gods") which

speeded the process. Further, it was intensified by the developing mechanisms

of group schema, development of language and cultural conformism (Boyd

and Richerson, 1985, 1990).

It should be obvious that group selection by meta-selection as described

here is different from earlier versions, the most important version being

the one defended most systematically and eloquently by Sober and Wilson

(1998).

The hypothesis of meta-selection was discussed on several forums (e.g.,

Knobloch ,1996, 1997) and in print (Knobloch, 1996; Barkow & Knobloch,

1996; Wilson & Knobloch, 1997). For exmaple, Dr. Barkow agreed with

me that, psychologically, a small social group is a model of all social

systems:

…intrapsychically, there are only small groups - it does not matter if

the reality is that we are dealing nation-states or with groups of evil

spirits, our psychology evolved in a small-group context and that is how

we conceptualize and react emotionally, in terms of small groups.

However, Dr. Barkow was cautious about the meta-selection hypothesis and

pressed for empirical data:

The most important problem is an empirical one - how to demonstrate that

leaders do enforce the values you say they do, and how to demonstrate

that their followers enhance their genetic fitness by accepting the influence

of the leaders. One empirical approach might be that of Betzig's despotism

work - she shows that the men at the top have immense reproductive success;

you would have to show that the middlemen/loyal followers have greater

fitness than the rebels.

It was rewarding that in the discussions, no serious flaws were found

in the meta-selection hypothesis. However, the general attitude was cautious

-it would surprising if it would be otherwise. The hypothesis will require

huge work both conceptually, and in collecting empirical data, to be accepted

or rejected. After all, it took one hundred years, before his idea of

sexual selection, which Darwin himself added to natural selection, was

generally accepted (Cronin, 1991, 123-243).

SUMMARY

According to the meta-selection hypothesis which posstulates a speckal

kind of group selection, organized and cohesive human groups became higher-level

breeders. These higher-level breeders had selective power to manipulate

their members, by a rewards-costs system of social exchange, in such a

way that altruism beyond reciprocity, which originally was a handicap,

became a potential fitness advantage for those who were able to strike

a balance between altruistic attitudes resulting from meta-selection and

self-interest resulting from natural selection. The relationship among

non-kin members within a group became more similar to that among kin members

vis-a-vis altruism beyond reciprocity, social exchange became flexible

in its exchange rates, following cultural norms, and group schema developed

as an instrument for the fine-tuning of social adjustment and the tightening

of group control over private life.

A fragment of a discussion with Barkow gives an idea how complex and arduous

the testing of the meta-selection hypothesis will be. But whatever the

results of testing will show, it is hoped that the theme of meta-selection

opens new alternatives for thinking about the old puzzles of altruism,

self-sacrifice and self-restraint which will stimulate both evolutionary

psychologists and psychoanalysts striving as they strive for a deeper

and unified understanding of human nature.

NOTES.

NOTE 1. TRANSFERENCE AND EVOLUTION. The importance of transference for

evolutionary theory is that transference means the shift of relationship

from a kin member, usually a member of one's nuclear family, to a non-kin

person. But Freud not only drew attention to the fact of transference,

he designed an ingenious, yet deceptively simple technique, which can

be easily converted into an experimental technique, and which amplifies

transference and makes it manifest: psychoanalytic technique itself. (The

patient is relaxed on a couch, free-associating, with the therapist out

of sight and reacting minimally, depriving the patient of a significant

degree of social feedback. The restriction of feedback forces the patient

to substitute it by an assumptive feedback and - most significantly -

ascribe to the analyst the characteristics and reactions of significant

persons from childhood, in particular, parents.) This quasi-experimental

technique reveals how surprisingly easy it is for human beings to shift

attitudes and feelings from a kin member to a non-kin person.

In some ways, the object fixation of non-human animals is more rigid.

Imprinting in birds determines the life-long recognition of conspecifics

and even later the recognition of sexual objects, which may lead to the

bizarre choices of humans or human-related objects present during hatching

(e.g., a bird may court the boots of an experimenter). Some breeds of

dogs, attached to a person in a sensitive period, are bound for life;

if the human disappears, they become permanently demoralized (Lorenz,

1961).

Although there is a rich body of literature on the relationship of psychoanalysis

and evolutionary theory (e.g., Bacciagaluppi, 1989, 1994, 1998; Badcock,

1986; Glantz & Pears, 1989; Slavin & Kriegman, 1992; and Wenegrat,

1984), the significance of ttransferencee for evolutionary theory has

not been to my knowledge discussed as possibly one of the most important

contributions of psychoanalysis to evoluytionary theory.

NOTE 2. SOCIAL EXCHANGE

The empirical basis of Freud's psycho-economics was his observation about

the strength and direction of motivational pressures, pressures similar

to vectors which support or conflict with each other. If we accept, as

is suggested here, that psychodynamics are basically private sociodynamics,

it takes us naturally to social exchange theories, inspired, as in Freud's

case, by economic thinking. As might be expected, the range of values

people exchange is much broader than those dealt with in economics, and

entails goods, services, status, love, information and money (Foa and

Foa, 1976). As mentioned above, group schema represents a "parallel

market of imaginary values," resulting in rewards and costs - for

example, a good or bad conscience.

Cosmides (1989) has examined social exchange in evolution. She means by

it "cooperation between two or more individuals for mutual benefit"

(p. 52). She argues that as part of the development of social intelligence,

and as an important instrument of differential survival in humans, a special

module developed in evolution which assesses the cost-benefit exchange

of values and detects people who cheat on social contracts - she labels

it a "Darwinian algorithm."

Social exchange is regarded here as an important instrument of meta-selection,

motivating to pursue equitable, fair and just transactions. But whereas

the basis of social exchange is, according to the hypothesis of Cosmides,

an Darwinian algorithm, the exchange rates are flexible and determined

by culture.

Note 3: GROUP SCHEMA In our past, we lived 99 per cent as hunters-gatherers,

in small groups of some 30 persons. Individual and inclusive fitness has

always correlated with the capacity of social adaptation. So not surprisingly,

" individual psychology is at the same time social psychology"(Freud,

1921, p.18). And we live in a small social group 24 hours a day, since

our social reality is freely copied in our "virtual reality,"

our dreams and day dreams. Our schematic group we live in I named group

schema (Knobloch, 1963; also this Journal, Knobloch & Knobloch, 1979a).

It is akin to later developed concept (as noticed by Bacciagaluppi, 1994)

of Bowlby's "internal working models, 1979, p. 469. It is composed

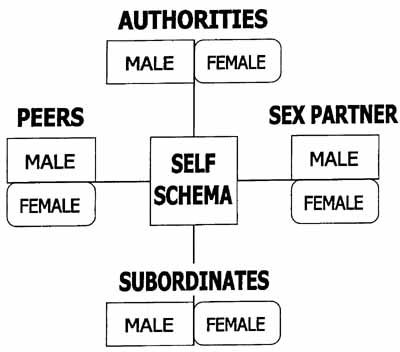

of role schemas: male-female authorities, male-female peers, male-female

subordinates and male-female intimate/sexual partners. (Figure 1.) The

group schema has three functions. First, it is a cognitive map instructing

how to behave toward persons in different roles; it is mostly beneficial,

but can be harmful, as in self-defeating behavior based on self-fulfilling

prophecies. Second, it is a playground for fantasy and trial exploration

in problem solving (Freud's probeweises Handeln, trial acting). It is

most vivid in dreams and daydreams, but operates in the background of

our consciousness all the time. And, finally, it is a parallel market

of social exchange, providing imaginary benefits and costs. The reasons

for this formulation, avoiding the intrapsychic-interpersonal fallacy,

were explained also in this Journal (Knobloch & Knobloch, 1979a).

Group schema is regarded here as an important instrument of meta-selection.

Through the group schema, the society controls the mental life of a person

24 hours a day, it is a way of "self-domestication or "self-socialization".

An important assumption here is that role schemas and their interactions

are programmed in evolution, not only such obvious ones as mother-baby

or sexually attractive bodies, but also others as well developed in hominoids-

such as the ritualized interactions of subordinate chimpanzees with the

alpha male, reminiscent of ceremonies at a despotic emperor's court. The

innate elements of role schemas are what the ethologists Lorenz and Tinbergen

called innate releasing mechanisms or social releasers (originally called

innate schemas), responded to by fixed action patterns (Lorenz, 1981).

The group schema has similarity with Harlow's (1971, 1983) affectional

systems described in rhesus monkeys, but in principle the same according

to him in all primates. The secure attachment between a baby monkey and

the mother is necessary for the next step of socialization, a healthy

relation with peers, which in turn makes possible the relationship with

sexual partners. A disturbed bond between a baby and its mother in early

childhood leads to disturbed relationship with peers and later with sexual

partners, often resulting in unsuccessful mating and failure in mothering.

The role schemas are akin to Sullivan's personifications and they can

be called, with Jung, archetypes. Though basically programmed by evolution,

they are highly individualized in ontogenesis, and, as Freud showed, molded

by early relationships, in a process reminiscent of imprinting in other

animals.

Figure 1. Group schema

Group schema reflect the structure of the small social group and is

composed of role-schemas of Self, Authorites, Peers and Intimate/Sexual

Partners. Programmed in evolution, highly individualized ontogenesis.

Acknowledgements. I thank Richard Marcuse for editorial assistance in

the preparation of this paper, a short version of which was presented

at the Ninth Annual Meeting of the Human Behavior and Evolution Society,

Tucson, Arizona, June 4-8, 1997.

REFERENCES

Alexander, R.D. (1979), Natural selection and social exchange, in R.L.Burgess

& T. L. Huston (eds.), Social Exchange in Developing Relationships,

Academic Press, New York, pp. 199-221.

Bacciagaluppi, M. (1989), Attachment theory as an alternative basis of

psychoanalysis, J. Am. Acad. of Psychoanal., 49 (4), 311-317.

Bacciagaluppi, M. (1994), The relevance of attachment research to psychoanalysis

and analytic social psychology, J. Am. Acad. of Psychoan., 22, 465- 479.

Bacciagaluppi, M. (1998), Recent advances in evolutionary psychology and

psychiatry, J. Am. Acad. Psychoanalysis, 26, 5-13.

Badcock, C. R. (1986), The Problem of Altruism: Freudian-Darwinian Solutions,

Blackwell, Oxford.

Badcock, C. R. (1998), Psycho-Darwinism: The New synthesis of Darwin and

Freud, in C. Crawford & D. L. Krebs (Eds.), Handbook of Evolutionary

Psychology, L. Erlbaum, Mahwah, N.J.

Barkow, J. M. and Knobloch, F. (1996), Natural, sex, and system selection

(Discussion), ASCAP, 9(8), 13-16.

Batson, C.D., and Shaw, L. L. (1991), Evidence of altruism: Toward a pluralism

of prosocial motives, Psych. Inquiry, 2(2), 107-122.

Bleueler, E. (1919), Autistic-Undisciplined Thinking in Medicine, Haffner,

Darien, Conn., 1969.

Boyd, R. (1992), The evolution of reciprocity when conditions vary, in

Coalitions and Alliances in Humans and Other Animals, A.H. Harcourt and

F.B.M. de Waal Eds.), Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 473-489.

Boyd, R., and Richerson, P.J. (1985), Culture and the Evolutionary Process,

University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Boyd, R., and Richerson, P. J. (1990), Culture and cooperation, in J.

Mansbridge, Beyond Self-Interest, University of Chicago Press, Chicago,

pp. 11-132.

Caporael, L.R., Dawes, R.M., Orbell, J.M., and von de Kragt, A.J.C. (1989),

Selfishness examined: Cooperation in the absence of egoistic incentives,

Behavioral & Brain Sciences, 12, 683-739.

Cosmides, L. (1989), The logic of social exchange: Has natural selection

shaped how humans reason? Studies with the Wason selection task, Cognition,

31, 187-276.

Cosmides, L, and Tooby, J. (1992), Cognitive adaptations for social exchange,

in J. H. Barkow, L. Cosmides and J. Tooby (eds.), Adapted Mind: Evolutionary

Psychology and the Evolution of Culture, Redford Press, New York, pp.

163-228.

Darwin, C. (1859), The Origin of Species, New York, A Mentor Book, 1988.

Darwin, C. (1871), The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex,

Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J., 1981.

Dawkins, R. (1976), The Selfish Gene, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dawkins, R. (1989), The Selfish Gene, New edition, Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Edelman, G. (1992), Bright Air, Brilliant Fire: On the Matter of the Human

Mind, Allen Lane, London.

Foa, E and Foa, U. (1976), Societal Structures of the Mind, C. C. Thomas,

Springfield, Ill.

Frank, R. H. (1988), Passions within Reason: The Strategic Role of Emotions,

Norton, New York.

Frank, R. H. (1991), Economics, in M. Maxwell (ed.), The Sociobiological

Imaginations, State University of New York Press, New York.

Freud, S. (1912), The dynamics of transference, Standard Ed., International

Universities Press, New York, 1966, 12, 97-108.

Freud, S. (1921), Group psychology and analysis of the ego, Standard Ed.

18, 16-143.

Freud, S. (1940), Outline of psychoanalysis, Standard Ed. 23, 183-208.

Fromm, E. (1962), Beyond the Chains of Illusion: My Encounter with Marx

and Freud, Simon and Schuster, New York.

Glantz, K. and Pearce, J. K. (1989), Exiles from Eden, Norton, New York.

Goldstein, D.S. (1995), Stress, Catecholamines and cardiovascular Disease,

Oxford University Press, New York.

Gottman, J., Notarius, C., Markman, H., Bank, S., Yoppi, B. and Rubin,

M.E. (1976), Behavior exchange theory and marital decision-making, J.

of Personality and Social Psych., 34, 14-23.

Boulder, A. (1969), and The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement,

Am. Social. Rev., 47, 75-80.

Harlow, H.F. (1971), Learning to Love, Albion, San Francisco.

Harlow, H.F. and Novak, M.A. (1973), Psychopathological perspectives,

Perspect. Biol. Med., 16, 461.

Homans, G. C. (1971, 1974), Social behavior: Its elementary Forms, Harcourt

Brace Jovanovitch, New York.

Hrdy, S. (1994), An interview, in T. A. Bass (Ed.), Reinventing the Future:

Conversations with the World's Leading Scientists, Addison-Wesley Publishing

Company, Reading, Mass., pp. 7-25.

Huston, T.L. and Burgess, R.L. (1979), Social exchange in developing relationships:

An overview, in T.L. Huston and R.L. Burgess (Eds.), Social Exchange in

Developing Relationships, Academic Press, New York.

Kelley, H.H (1979), Personal Relationships: Their Structures and Processes,

Lawrence Erlbaum, New York.

Kelley, H. H. and Thibaut, J. W. (1978), Interpersonal Relations - A Theory

of Interdependence, Wiley, New York.

Knobloch, F. (1963), Osobnost a malá spoleeenská skupina, (Personality

and small social group), Československá psychologie, 5 (4), 329-337.

Knobloch, F. (1968), Toward a conceptual framework of group-centered psychotherapy,

in, B.F. Riess (Ed.), New Directions in Mental Health, Grune & Stratton,

New York.

Knobloch, F. (1985), Group schema: Toward a psychodynamic-behavioral integration,

in P. Pichot, P. Berner, R. Wolf and K. Thau (Eds.), Psychiatry: The State

of the Art (Proceedings of the VIth World Congress of Psychiatry), Plenum

Press, New York.

Knobloch, F (1996), Individual, group or meta-selection? Mental life as

a small group process, ASCAP, 9(6), 15-18. (Presented at the ASCAP Conference,

New York, May 5, 1996 and as a Poster Presentation, The Eighth Annual

conference of the Human Behavior and Evolution Society, Evanston, Ill.,

June, 1996.)

Knobloch, F. and Knobloch, J. (1979a), Toward a new paradigm of psychoanalysis,

J. Am. Acad. of Psychoan., 7, 499-624.

Knobloch, F. and Knobloch, J., (1979b), Integrated Psychotherapy, Jason

Aronson, New York.

Knobloch, F. and Knobloch, J. (1982), Therapeutic community and social

exchange theory, in M. Pines and L. Rafaelson (Eds.), The Individual and

the Group (Proceedings of the 7th International Congress of Group Psychotherapy

in Copenhagen), Plenum Press, New York, pp. 529-541.

Knobloch, F and Šerfrnová, M. (1954), Příspšvek k technice rodinné psychoterapie

[A contribution to the technique of family psychotherapy], Neurologie

a psychiatrie československá, 17, 217-224. (English translation by N.I.H.,

Bethesda, Maryland, No. 2-3-62.)

Krebs, D.L. (1991), Altruism and egoism: False dichotomy?, Commentary

on Batson, C.D. and Shaw, L. L., Evidence of altruism: Toward a pluralism

of prosocial motives, Psychological Inquiry, 2(2), 137-139.

Lopreato, J. (1984), Human Nature and Biocultural Evolution, Allen &

Unwin, Boston.

Lorenz, K. Z. (1961), King Solomon's Ring, Thomas Y. Crowell, New York.

Lorenz, K. Z. (1981), The Foundations of Ethology, Springer, New York.

McGuire, .

Maynard-Smith, J. (1998), The origin of altruism, Nature, 393, 18 June

1998), 639-640.

Mook, D.G. (1991), Why can't altruism be selfish?, Commentary on Batson,

C.D. and Shaw, L. L., in Evidence of altruism: Toward a pluralism of prosocial

motives, Psychological Inquiry, 2 (2), 139-141.

Pollard, P. (1989). Natural selection for the selection task: Limits to

social exchange theory, Cognition, 35, 195-204.

Schafer, R. (1972), Internalization - process of fantasy?, Psychoanalytic

Study of the hild, 27, 411-436.

Selye, H. (1956), Stresses of Life, McGraw Hill, New York.

Slavin, D. and Kriegman (1992), The Adaptive Design of the Human Psyche:

Psychoanalysis, Evolutionary Psychology and Therapeutic Process, Guilford,

New York.

Sober, E. (1994), Models of cultural evolution, in E. Sober (Ed.), Conceptual

Issues in Evolutionary Biology, Second Edition, MIT Press, Cambridge,

Mass.

Sober, E. and Wilson, D. S. (1998), Unto Others: The Evolution and Psychology

of Selfish Behavior, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Soltis, J., Boyd, R. and Richerson, P.J. (1995), Can group functional

behaviors evolve by cultural group selection?, Current Anthropology, 36(3),

473-493.

Sullivan, H.S. (1953), The Interpersonal Theory of Psychiatry, W.W. Norton,

New York.

Sullivan, H.S. (1964), The Fusion of Psychiatry and Social Science, W.W.

Norton, New York.

Thibaut, J.W. and Kelley, H. H. (1959), The Social Psychology of Groups,

Wiley, New York.

Thiessen, D. (1996), Bittersweet Destiny, Transaction Publishers, New

Brunswick, New Jersey

Tooby, J. and Cosmides, L. (1989), Evolutionary psychologists need to

distinguish between the evolutionary process, ancestral selection pressures,

and psychological mechanisms, Behavior and Brain Sciences, 12 (4), 724-725.

Trivers, R. L. (1971), The evolution of reciprocal altruism, Quarterly

Review of Biology, 46, 35-57.

Trivers, R. L. (1985), Social Evolution, Benjamin Cummings, Menlo Park,

California.

Trivers, R.L. (1999a) Review of Sober & Wilson's book, Unto Others,

Skeptic Magazine 6(4)

Trivers, R.L. (1999b) Think for yourself!, Skeptic Hotline, Skeptic Magazine,

6(4), 62-73.

de Waal, F. (1982), Chimpanzee Politics, Harper & Rowe, New York.

de Waal, F. (1989), Peacemaking among Primates, Harvard University Press,

Cambridge, Mass.

de Waal, F. (1992), The Chimpanzee's sense of social regularity and relation

to the human sense of justice, in R. D. Masters and M. Gruter, (Eds.),

The Sense of Justice. Biological Foundations of Law, Sage Publications,

Newbury Park, London, pp. 241-255.

de Waal, F. (1996), Good Natured, Harvard University Press, Cambridge,

Mass.

Wilson, D. S. (1989), Levels of selection: An alternative to individualism

in biology and the human sciences, Social Networks, 11, 357-272.

Wilson, D.S. (1996), Adaptation and individual differences, Presentation

at the Eighth Annual conference of the Human Behavior and Evolution Society,

Evanston, Ill., 1996.

Wilson, D.S. and Knobloch, F. (1997), Meta-selection, Exchange debate,

ASCAP, 10:(1), 11-12.

Wilson, D.S. and Sober, E. (1994), Reintroducing group selection to the

human behavioral sciences, Behav. and Brain Sciences, 17: 585-654.

Wilson, D.S. and Sober, E. (1999), The golden rule of group selection,

Reply to Robert Trivers, Skeptic Hotline, Skeptic Magazine, 6(4). 62-72.

----