ČLÁNKY, TEXTY K IP

My study of the significance

of music has been slowly progressing since the early sixties 1,2,3, as

a by-product of my psychotherapeutic work, particularly in a therapeutic

community 4 viewed as an ethological laboratory.

Musical experience

as interpersonal process

The cliché "music is expressing feelings", though true, always has

seemed to me to be a mind-stopper, preventing a broader understanding

of the meaning of music. As in a dream, music creates a fantasy world.

It elicits in us tedencies towards others, and lets us feel the impact

of their tendencies. In other words, music creates interpersonal situations

in which we participate, although the narrative is only schematic and

does not describe any concrete situation. Suppressing the tendency to

speculate-not unknown in the field of esthetics- I designed a simple experiment

to test the hypothesis that music has interpersonal meaning, which

is basically the same for different people.

A military march played to soldiers going to war is designed to support

their optimistic attitude of self-confidence, dominance, pride, showing

off and aggression. Such music makes us to identify with its tendencies.

The result could be quite different if these tendencies would be presented

iinstead visually, in posters -- such as pictures of aggressive men who

shoot. Rather than identifying, we would likely have a complementary

reaction -- being pushed into submission, feeling attacked, feeling fear

and running away. The same happens when we hear such music in sleep: we

usually do not identify with it, we feel the dominant and aggressive impact

which pushes us into complementary reactions of submission, avoidance,

fear and flight. In a waking state, music can create both identification

and complementation -- but most of the time it creates identification.

Hypothesis testing: the musical circumplex

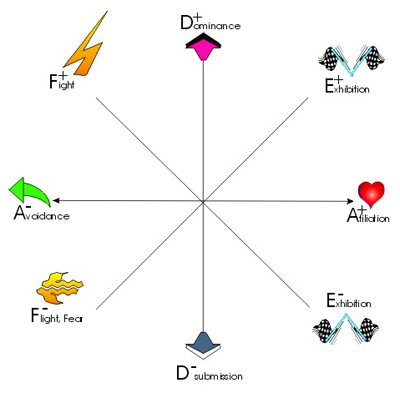

In the first experiments, Leary's 5 circumplex with its eight tendencies

was used. But soon, listening to music and ibeing nspired by ethology

(e.g., I missed flight, fear), I changed it. The circumplex (Table and

Picture) has a horizontal (afiliation-avoidance) and a vertical (dominance-submission)

axes.

The tendencies

are:

D+ DOMINANCE: Directs, dictates, advises, controls

D- SUBMISSION: Asks for or accepts direction, dictate, advice, control

E+ EXHIBITION+ : Displaying a supposedly valuable quality: I am powerful,

attractive, intelligent, have high status, etc.

E-: EXHIBITION- : Sympathy-, care-, pity-soliciting -- displays a lack

of some quality- I am needy, weak, suffering, ill, depressed

A+ AFFILIATION: Approaches, seeks cooparation, closeness, friendship,

attachement, love

A - AVOIDANCE : Avoids contact, seeks isolation, distance, detach ed

F+ FIGHT : Attacks, shows anger, hostility, aggression

F- FLIGHT : Tries to escape from danger; fears

Since the hypothesis tested deals exclusively with the question of the

interpersonal meaning of music, questions about the psychometric properties

of the circumplex are not important here (such as: Is it psychomentrically

well ordered? -- as, e.g., J. Wiggins 6 tries to achieve -- or the question:

Is the basic idea of interpersonal circumplex psychometrically sound?,

raised by J.D. Jackson 7 "the circumplex structuring is too simple...inconsistent

with much of modern measurement theory" [6])).

Two tests were used, consisting of 24 and 17 fragments respectively of

European music from the seventeenth to the twentieth centurcies. They

were presented to the ESs who independently answered which tendency or

tendencies they found in each fragment. In the first experriment there

were 3 ESs, in the second 59 and in the third 3 again. In the statistical

evaluation the null hypothesis ("the answers are random") was rejected

on 5% level of confidence in the first and on 1% level of confidence in

the second and third experiment.

Numerous subsequent unpublished experiments both from Europe and North

America showed the same results. The same has been reported by others

(e.g., the musicologist J .Doubravova, 8 .). It is concluded that in

the populations studied, music has basically the same interpersonal meaning

for all people.

Cultural and biological programming

What gives the music its universal meaning? One part of the agreement

about music among listeners is, no doubt, cultural. If one hears organ

music, one thinks about church, something sacred or religious-but only

in certain cultures of the world! On the other hand, some aspects of music

seem to ne universal. Nobody will think about lovers in moonlight or a

sleeping baby when hearing the loud and quick beats of drums or sounds

of loud trumpets. Some sound patterns, such as laughter, crying, male

and female voice, are believed to be evolutionary programmed social releasers

(Lorenz) and are imitated in music by different instruments (flute, violin,

violincello, etc.), possibly as supernormal stimuli. Supernormal stimuli

(K.Lorenz 9) are artificial stimuli which have greater impact as social

releasers than natural stimuli. (E.g., an artifical egg four times larger,

but with a clearer black-and-white pattern than the real eggs of the bird

ring plover is preferred by the parent bird, which throws out of the nest

its own eggs in favor of the artificial eggs.- A gape of the parasitic

cuckoo nestling has a hi gher stimulus value for the parent birds than

of their own nestlings.) Music has in some respects similar complex structure

as language -- possibly sharing with it its "deep structure" (Chomsky)..

The interpersonal character of music is, of course, not the only important

aspect of music. Though this will be likely different in future, the present,

rather simplified interpersonal analysis is not in a position to contribute

to the assessement of the esthetic quality of music. Also, the interpersonal

reactions of people of different cultures have to be studied much more

extensively than has been possible so far. However, the method can be

used already now for studying objectively, e.g., how the musical interpersonal

spectrum of a composer changes during his/her life, and how the spectra

of different composers and of different musical epochs differ. Also the

difference between poetry and music can be studied. For example, there

is a discrepancy in renaissance madrigasls, e.g., those of Orlando di

Lasso, between the text expressing strongly E-("I am desperate and suffering),

and the lack of E- in the accompanying music. And only three decades later,

the E- tendency is strongly expressed both in the text and music in the

madrigals of Carlo Gesualdo, that passionate partisan of chromaticism

and jealous killer of his wife.

What would Nietzsche say today?

When talking about biologicall programming of music, one must think about

Friedrich Nietzsche, who claimed that esthetics is "nothing but a kind

of applied physiology" and explained:

What is it that my whole body really expects of music....? I believe,

its own ease: as if all animal functions should be quickened by easy,

bold , exuberant, self-assured rhythms; as if iron, leaden life should

lose its gravity through golden, tender, oil-smooth melodies. My melancholy

wants to rest in the hiding places and abysses of perfection: that is

why I need music.(10]

Today, when evolutionary biology and physiology invaded the territory

of interpersonal relations, Nietzsche might talk about esthetics as applied

ethology or sociphysiology . Encouraged by what he said at different times,

but still with trepidation and apologies to Nietzsche, I will take the

risk and say loud my guess what he might say:

" I, Zarathustra, descended from my mountain because I love people,

that rope between the ape and overman. I am with people all the time --

whether they are real or my phantoms. We are connected -- indirectly by

the illusive bridges of words, and directly by music, dance and laughter.

What is it that my whole body expects from music? Its own ease: as if

all animal functions in me and my friends- love, anger, pride , sadness-

were quickened, and I could reach the essence of people as never before.

Music makes me slip into the dramas and tragedies of others' lives --

and for a while I am even seduced into believing that these concrete scenes

reveal the meaning of music. But that is how music teases me. The scenes

are only illusions, reflections on water. The paradox of music is that

it is a universal language -- and yet, the universality is not an empty

universality of abstraction. Music talks directly to my senses and my

body and reveals the true nature of human beings."

Interpersonal

analysis of music may bring us not only closer to the understanding of

music and arts, but also to the understanding of the depths of human nature.

REFERENCES

1 Knobloch,F& Postolka M & Srnec, J (1964). Musical experience

as interpersonal process. PSYCHIATRY: J. for the study of interpersonal

processes, 27:4, 259-265.

2 Knobloch et al (1968). On an interpersonal hypothesis in the

semiotic of music. Kybernetika, Prague, 4:4, 364-382.-Experiencia musical

como processo interpersonal. Una contribucion a la teoria de la musica.

In:Rojas-Bermudes JG(Ed.), Cuadernos de Psicoterapia. Buenos Aires: Associacion

Argentina de Psicodrama y Psicoterapia de Grupo. VII:1-2, 1972-3.

3 Knobloch, F. (1998). Musical experience as interpersonal process:

Revisited. In: R. Monelle (ed.) Musica significans (Proceedings of the

International Congress on Musical signification, Edinburgh, 1992). Contemporary

Music Review 17. 2: 59-72.

4 Knobloch F. & Knobloch J. (1979). Integrated Psychotherapy. New

York: Jason Aronson. - Stuttgart: F. Enke, 1983 (German) -- Tokyo: Seiwa

Shoten 1984 (Japanese) -- Praha:Grada, 1993(Czech) -- Shantou University,

1998 (Chinese).

5 Leary T. (1957).Interpersonal diagnosis of personality. New York:

The Ronald Press.

6 Wiggins J & Pincus AL.(1992). Personality structure and assessement.

Annual Review of Psychology, 43, 437-504.

7 Jackson DN & Helmes E.(1979). Personality structure and the circumplex.

J. Personality and Social Psychology, 37: 12, 2278-2285.

8 Doubravova J.(1972). Alban Berg's violin concerto from an interpersonal

point of view (In Czech). Hudebni veda, Praha, 9(2), 107-139.

9 Lorenz K.(1981). The foundations of ethology. New York: Springer,.

10 Nietzsche, F. (1888/1968). Nietzsche contra Wagner. In: W. Kaufmann,

The portable Nietzsche. New York: the Viking Press., p. 664

Ferdiand Knobloch, MD, FRCP(C)

Professor

Emeritus of Psychiatry University of British Columbia

4137 W 12 Ave Vancouver, B.C., V6R 2P5 knobloch@interchange.ubc.ca